China India Networked #2 ft. 🇮🇳 🏥 🇨🇳 Indian Pharma in China

A newsletter highlighting the "networked" relationship between China and India through translations, curated reading, and commentary.

Welcome to issue #2 of China India Networked, a bi-weekly newsletter by me, Dev Lewis, highlighting the networked relationship between the two regions through local voices at the intersection of technology, society, and politics.

I’m grateful to all of you that subscribed, and to have received several encouraging messages. Please keep the comments and suggestions flowing. If you were forwarded this, sign up for regular posts to your inbox using the button below.

Today’s issue is very much in the ‘China-India’ mold. We have an in-depth piece on the longstanding struggles of Indian pharmaceutical companies in China, and why they may be on the verge of turning a corner.

This week news broke that Chairman Xi Jinping will visit Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu from October 11-13 for an “informal” summit with Prime Minister Modi.

This means we’ll see a gradual dialing up in India-China coverage across both Chinese and Indian media over the next 5-6 weeks. In Indian reporting we’ll see all the usual suspects raised, including the large trade deficit (popular well before Trump)—currently US$ 50+ billion—attributed to “market access and regulatory barriers” faced by Indian IT and Pharmaceutical companies. Rarely do we see any evidence-based reporting unpacking this with balance or nuance, representing views from industry or government in China. While Indian IT has at best an extremely weak case, Indian pharma does have one—supported by a long-standing demand from the Chinese public (how many Indians living in China have at one point been asked by Chinese friends and colleagues to help carry cancer treatment drugs?).

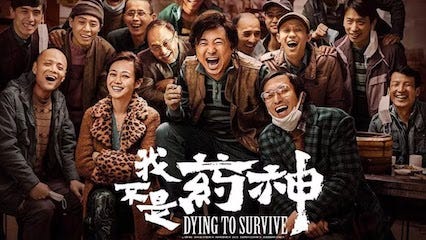

In June last year, Chinese film Dying to Survive (highly recommend!) spurred a national discussion on this topic. That the movie, which does not show the authorities in the best light, made it to the big screen was a sign that domestic changes were afoot. This past Monday the National People’s Congress approved a revision in drug laws so that foreign generics are no longer treated as “fake medicine”. Regulations are just one part, execution and adapting on the part of Indian pharma companies is just as critical—as this week’s piece touches on. So read on!

The China India Networked Newsletter is by me, Dev Lewis. I’m a Fellow at Digital Asia Hub and Yenching Scholar at Peking University, where i’m conducting research on the Social Credit System and data governance. Follow me on Twitter @devlewis18 or write to me at devlewis@protonmail.com

After a Lost Decade, Indian Pharma begins a New Campaign Armed for Success, by Suping Ma and Sizhou Huang, journalists at China Southern Weekly, tells a story of Indian pharma in China: failures over the past decade, renewed cross-border engagement, and a light at the end of the tunnel that may be visible.

Big moves in 2019:

Joint-ventures announced: Cipla Europe-Jiangsu Ceno; Strides- Sihuan Pharma; Sun Pharma-Kangzhe Pharma.

Two agreements on generic drugs and innovative product patenting.

Netco Pharma to launch clinical trials for its popular cancer treatment drug.

The first China-India Drug Regulatory Exchange Conference held in Shanghai in 2019 towards harmonising the entry of Indian medicine into China.

Why now? Where have been the failings for the past decades?

Ranbaxy established the first Sino-Indian JV in 1993 only to exit in 2009.

Only about 200 Indian medicines officially listed in China, most of them of the 'unprocessed' type. In the past two decades only 45 Indian finished drugs have been approved in China, none of which are anti-cancer drugs.

🇨🇳 🗣

Indian pharmaceutical companies have failed to establish themselves in China because they could not truly localise…“believing that they are compliant with European and American standards, for years they only provided registration information of the Europe and the United States and did not comply with Chinese registration regulations and data requirements. Their application materials are therefore often found not in compliance and rejected." —Meng Dongping, vice president, CCCMHPIE.

🇮🇳 🗣

The lengthy process of 3-5 years scared off many Indian pharmaceutical companies."We wanted to export medicines to China, and after filing for registration we never heard back and were in the dark"— head of a Chinese representative office of a Indian pharmaceutical company.

Indian pharma fails to localise

For example, in China, generic drugs cannot enjoy the same pricing privileges as patented original drugs. Once in China, in order to avoid conflicts with existing varieties on the market, it takes a lot of pain staking effort to selected among many others…if you want to compete with the original pharmaceutical companies and local companies, you need to a partner to work together with, including in marketing and operations.

Things are turning around…

Potential in a new 4+7 - a new volume based procurement program: For imported generics, one of the best ways to pick up market share is to participate in national centralized procurement. It has been reported that Indian generic drug companies have been negotiating to participate in the “4+7” volume based procurement, some pharmaceutical companies said that they could lower prices could by a further 20%-30% based on the bid price. The “4+7” volume purchase can be understood as a large-scale “group purchase” in 11 pilot cities, where the winning bid is guaranteed 70 % of the market in the city. The volume of each the purchase enables a more optimal the price between competing enterprises.

“The entry of Indian pharmaceutical companies in China is the next big game”, says an executive from Nanjing Zhengda Tianqing Pharmaceutical in his analyses. By entering China through the JV route, on one hand they will have the product advantage that can seize a considerable portion of the market through the 4+7 procurement. On the other hand, with the guiding hand of their local partner they can introduce more high-margin products. This will huge impact on domestic pharmaceutical companies.

Challenges ahead:

To participate in the “4+7” volume based procurement, Indian pharmaceutical companies still need to cross several thresholds – such as getting their drugs approved by the State Food and Drug Administration. In addition, volume based procurement is evaluated by consistency in quality and efficacy. At present there is no such evaluation of generic drugs in India.

Clearly, its complicated. Few industries come more convoluted than healthcare and pharma. And there are some areas that this piece doesn’t get to, like domestic lobbies resistant to competition.

Changes are afoot. IF Indian companies play their cards right, they can not just put a big dent on the much talked about trade deficit (too bad you can’t count Yoga and Bollywood). They can bring a more affordable and better life to the millions of Chinese cheering them on—where can you find a better China-India feel-good story?

If you were forwarded this, sign up for regular posts to your inbox using the button below. Please consider forwarding to friends and sharing on social media, it means a lot when you do!

PS—readers that know more about Indian pharma in China please write in with your comments or more readings. I’m eager to learn more on a subject I know very little. I’ll try and feature them in the next issue.

The views expressed in this newsletter are mine and not representative of Digital Asia Hub as an institution.